FOUR YEARS AFTER THEIR election pledge to address housing unaffordability, and ten years after the housing bubble began to seriously inflate, the National Government is finally making noises about the problem.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure they’re the right noises.

Short on specifics as yet—apparently there is a paper being submitted to Cabinet today outlining “a multi-pronged work programme” issued in response to the Productivity Commission's report on this issue,* after which we might perhaps learn more—and not a peep has been heard out of housing minister Phil Heatley—so all we have to go on presently are the noises about this made over the last week and weekend by Finance Minister Bill English. And those noises are not altogether encouraging.

English identifies housing affordability as a problem, yet his characterisation that the "housing market is not working properly” is neither accurate nor helpful. The housing market is working as well as it can within the shackles and costs placed on it by government and councils. What is not working however are the planning, regulatory and rates burdens that constitute those shackles and add to the costs—such that between 1992 and 2012 the national average house price increased more than four times more than prices in general, which should ring warning bells.

IT IS ENCOURAGING THAT English is framing the debate around Hugh Pavletich’s annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Surveys,** which now show the median cost of a house in New Zealand is 5.2 times the median income in New Zealand, and in Auckland 6.4 times median income.

Any ratio above five is considered unaffordable [says English in last week’s Herald]. Despite demand for low cost houses, relatively few are being built - in part because of the very high cost of land, particularly in Auckland.

Yesterday on Q+A he expanded on that, recognising “there are a number of problems.”

One is the cost of building. That does appear to be pretty high, particularly compared to Australia. There's a lot of work being done on why that might be the case. More scale, building regulation - all of that can be improved, and that process is underway.

And while the cost of building materials sky-rocket, nothing proposed therein is going to make it easier to break what is essentially a “regulatory wall” of box-ticking making it almost impossible for NZers to use inexpensive foreign materials, or to enjoy the cost-savings of innovative building systems and techniques and systems. Systems like these Structural Insulated Panels, which are used in Canada, Europe, the US and Australia to great effect—low cost, low risk, low energy, huge insulation value, robust--but which are virtually impossible to build with here at home under our command-and-control building regulations that dictate virtually every detail of every new build.

There will be no innovations in NZ’s high-cost labour-intensive building techniques until innovative systems such as this can be painlessly introduced and exploited—perhaps only when councils themselves are taken out of the chain of responsibility for policing building standards…

“WE’RE ALSO CONCERNED about the supply of housing coming to the market,” English said on Q+A.

It does look like the councils have got a very difficult job ensuring that there's enough new land but also enough development within our cities of more dense housing to enable enough housing to come on to the market to stop prices rising unnecessarily.

Let’s be clear: it is not council planners who have the difficult job here; it’s the good folk trying to design and build within the rules dreamed up by those almost hysterically anti-development planners under the completely non-objective Resource Management Act.

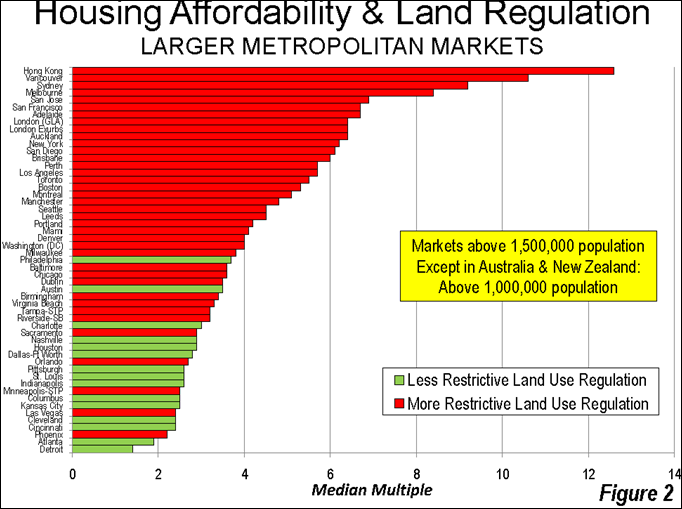

New Zealanders are being screwed on housing. If we compare Christchurch and Auckland with, let’s say, the housing markets of Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth,and Atlanta, using the same methodology employed by Demographia in their International Housing Affordability Surveys, what we find is astonishing—especially when correlated with the level of regulations on land.

By this measure, Auckland is the tenth-least affordable large metropolitan market in the English-speaking world. And virtually every city that has adopted so-called Smart Growth policies—restricting land use and ignoring property rights—has been made unaffordable thereby. Mostly because of those land regulations.

Fresh from whacking up rates on Aucklanders however, Mayor Len Brown has said he doesn’t see the problem. His planners have allowed land-owners enough land on which to build 18,000 houses in Auckland, he says, so what’s everybody bitching about?

What Mr Brown and his planners ignore is the costs of production. The cost of buying, servicing and producing houses on so many of those 18,000 sites are well above any realistic purchase price—even with the stratospheric purchase prices Aucklanders are somehow paying. That’s why so few of those 18,000 sites are not being built on, even if the planners have so kindly re-zoned them so they can.

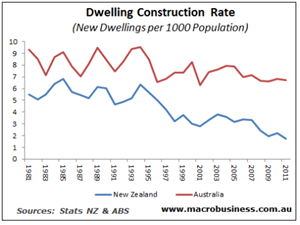

SO IT’S CERTAINLY TRUE to say “there are a number of problems.” But it’s not at all clear those problems are being addressed. Just look at where the huge cost increases happened over the first part of the housing bubble:

The key drivers of the housing affordability issue have been, in order of priority:

- rises in land cost,

- rises in local authority infrastructure levies and fees,

- increasing compliance costs, and

- increased labour and material costs.

The first two are directly related to local government and the Resource Management Act; to over-spending councils desperate to make up the shortfall on their rates take by dunning developers through fees and “development levies,” and to planners ring-fencing the outskirts of the city while making it impossible to build with increasing density within the city itself.

I really don’t think English has a clue how he’s going to change that. Consider this exchange on his appearance on yesterday’s Q+A:

CORIN DANN So councils don't seem that keen on the idea of urban sprawl here, the idea of building on the outskirts, because they have to fund the infrastructure to make that viable - the public transport, all that sort of thing. You want that? This is something you will push for in your response?

BILL And that's a fair enough concern from councils. In the end, the infrastructure's going to paid for by someone, either by development levies or by existing ratepayers or by the new homeowners. Often the problem is just timing and coordination. Can we get the infrastructure built a bit ahead of the market so that we can get the houses there when they're needed?

CORIN I'm just struggling - the changes that you're going to make, how are you going to incentivise for there to be more houses built in both those outskirts and also in the inner-city limits? What's the incentive?

BILL Well, look, the incentive for all of us is a more balanced economy with more investment available for jobs and growth, and the incentive for all of us is to avoid unnecessary debt. So our first job is to get a common sense of purpose here. It's not the government trying to tell the councils to do something they don't want to do. So get a common sense of purpose. And then we've got to look at what I have to say has turned out in my experience and, I think, others looking at it, a very complex interaction of planning and economics that lead to the incentives to build more or not. So what we've got to do is pick our way pretty carefully through that. We've got a couple of special opportunities - one in Christchurch, where, essentially, we can change all the rules if we really need to under the Earthquake Recovery Act. That's spurred some controversy, but we're learning a lot from making a lot more land available and changing the central city plan to create opportunities for all the people who lost their houses in the earthquake.

Corin Dann isn’t the only one struggling here. What on earth is there to learn from the complete clusterfuck the government has made out of Christchurch? They’ve used their dictatorial emergency powers to confiscate central city land, to prohibit home-owners from moving good houses off damaged land onto better land, and refused to do anything to remove council planners’ restrictions and prohibitions on desperately-needed new subdivisions.

Just last week an affordable subdivision in Dunn’s Crossing, Rolleston, was abandoned after planners refused to allow it to happen. This project was a non-profit making venture using a Cooperative Company Structure that would have delivered sections at a price of $35,000 less than the comparable market in Rolleston. This should have been a simple project to develop 18 affordable sections on a piece of quality land adjacent to existing residential housing. Planners however flatly said no. On behalf of the Trust trying to produce the subdivision, Simon White said

The failure of this project to provide affordable sections highlights the problems with the existing system of excessive restrictions on land use and overly complex and expensive processes and rules that apply to residential property development in New Zealand…The problem starts with the restrictive land use policies increasing the cost of land. We will consider another project if two conditions can be satisfied: 1. That affordable bare land can be acquired with a high certainty of being consented. At present this is not likely given the inflated prices of land in residential zoned areas; and 2. Seed funding can be obtained. This can be achieved but only if 1. above is achieved.

This is just one of hundreds of stories from Christchurch that could be cited.

So what is there to be learned from Christchurch, except what not to do!

Simon White points out what should be obvious even to politicians and mayors, that “as a result of the high costs and risks it makes sense for developers to target the higher priced market.”

Yet the likes of Labour’s Annette King can still jump into print bewailing “the tendency for new private sector-financed houses to be large and expensive,” and calling for more command and control: more government housing, more council housing, higher standards for rentals, and a capital gains tax to further sock developers already unable to see a clear a profit even with purchase prices as high as they are now.

Naturally, big-government worshippers like Bernard Hickey have echoed her call for more tax and more government, ignoring the evidence from overseas that capital gains taxes did nothing to help affordability, but less government has. (Virtually all of the top twenty most unaffordable markets in that graph at the top of the post had capital gains taxes and high govt involvement in housing.)

What it comes down to is choice. If people were only left free to live in the way they wanted -- however apoplectic that would make all the many enemies of choice -- the problems of housing unaffordability would disappear overnight.

BASED ON WHAT WE’VE already seen in Christchurch, I fear too that anything Bill does do to “free up” land will involve more confiscation rather than more choice and more freedom. Why do I say that? Because before the last election, Bill’s leader John Key signalled possible confiscation of land if developers refused to build on it when John Boy wanted.

I fear too that even if this outrage fails to come to pass (and don’t count against it), restrictions on private land won’t be removed, instead a few un-used “brownfield” sites (some of them perhaps previously confiscated from private land-owners) might be waved around by Bill English as a sort of large-scale photo opportunity to look like he’s doing something. And I say this because both Team Red and Team Blue were talking about that before the last election as a remedy for the increasing unaffordability of NZ housing.

British writer James Woudhuysen recently characterised this approach as "a kind of Army Surplus approach to housing."

‘Public sector land use’ ... turns out to be barracks, canals, railway sidings, and turf owned by the National Health Service (NHS) or by local councils. Here we are asked to scrape the bottom of a very small barrel. In effect, the [government] searches for the public sector bits of the 5.5 per cent of England’s surface that is brownfield land.

In effect, as Woudhuysen says, this amounts to little more than a little massaging of existing "ultra-restrictive land provisions" in the addled expectation it will have some effect. It won't.

The hope is that a tiny relaxation of planning constraints will encourage the private sector ... and numerous hybrid housing vehicles, state monoliths and quangos to build more homes, especially homes that are ‘affordable.’

That approach won’t work. It will mean some extra homes are built, but it will not make proper home ownership cheap.

No, it won’t. It won’t bring New Zealand builders home from Queensland, and it won’t do enough to lower land prices enough to build on. Something more radical is needed. Woudhuysen has such a proposal, one on which both Annette King and Bill English should sit up and take note. I paraphrase his proposal for a New Zealand audience:

Real homes will only become affordable if, in principle, everyone can go to a farmer, buy an acre of land for $30,000, and freely build a house there at a cost, perhaps, of just $100,000. That kind of transaction would lead to significantly lower prices than the $414,261 average asked for a home in NZ today.

The state should stop preventing deals like this from being done. It should step back, and instead provide the infrastructure to let that house-on-a-freely-bought-hectare thrive.

That such deals can't be done, and won't be done as a result of either Clark's or Key's announcements is a measure of the overbearing powers of the state in relation to the land.

Ever since the Town and Country Planning Act of 1927, to buy that $30,000 hectare of land and build on it has been illegal. The nanny state, not the popular will, determines who may build where. The state essentially retains a complete monopoly over what land can be developed for housing and what cannot. To end house price inflation therefore, Britain must end its state-imposed scarcity of land.

The lack of affordability that characterises Britain’s housing market is not about too many people – single-person households, divorced families, immigrants and their children – chasing too few homes. It is not simply an economic question of supply and demand. The housing market is profoundly distorted by the political intervention of the state, which imposes drastic limits on land that can be developed upon.

Only a similarly drastic counter-attack on state controls, amounting to a veritable bonfire of National's Resource Management Act and the country's forty-odd District Plans will allow housing in NZ to acquire a semblance of either rationality or efficiency.

What's needed in other words is neither massage nor spin, but the full-blooded planning revolution the destruction of NZ’s second-largest city should have encouraged; one that sees the country's planners joining the growing queues of the unemployed—and by their inclusion, shorten them.

NOW I CAN ALREADY hear the whining of anti-development zealots that such a common-sense dispensation as Woudhuysen proposes would see the whole country blanketed in houses. Bullshit.

NOW I CAN ALREADY hear the whining of anti-development zealots that such a common-sense dispensation as Woudhuysen proposes would see the whole country blanketed in houses. Bullshit.

As a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation would tells you, there would be no problem with sprawl if the ring-fencing were relaxed: New Zealand's existing urban areas account for less than 1 percent of the total country, one quarter of that in the Auckland region. Even if all of NZ's 1,471,476 existing households were to be rebuilt on an acre of land -- which was the sort of thing proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Broadacre project (right)—we'd all of us fit in an area less than one-quarter the size of the Waikato. (And just think how easy it'd be to thumb a lift out to Raglan!).

There’s more than enough room to go around. Especially out there on the Canterbury Plains.

SOLUTIONS LIKE WOUDHUYSEN’S are just one of many that can be applied by recognising that property rights are a solution, not a problem. It’s clear neither Hickey, nor King, nor English, nor Williamson no Key have any conception of how politicians and planners have caused the very “market failure” they bewail. Because while calling for government to fix the problem by doing more, they never even bothered to ask themselves whether it is government activity itself that has largely caused the problem.

And it has.

In a nutshell, the big problem is that government has gone beyond right: it has passed laws giving the Reserve Bank the power to print money, bureaucrats the power to prescribe the methods and materials by which houses are built, and planners the power to control and restrict people’s land.

Let’s look at these one at a time.

In recent years, the new money printed by the Reserve Bank (i.e., monetary inflation) has spilled over into the housing market, producing one housing “bubble” and thousands of NZers deluded into thinking their wealth has increased.

Meanwhile, the Department of Building and Housing were given the power to tell builders how to build houses. Rather than deregulation, which never happened here, builders have endured a flood of new regulation: producing pages and pages of gold-plated building regulations and a rise in the cost to build a house that has out-paced even the rate of house price rises.

And while the printing presses were going overtime printing new regulations and new money, the town planners were busy strangling land-owners and ring-fencing cities under the new powers given them by the Resource Management: the power, essentially, to restrict development of new, affordable housing while charging builders and developers more for the “privilege” of trying to build something on their own land.

Meanwhile, the planners’ employers in council were piling over-spending on over-spending, raiding developers’ pocket books to take up the slack.

The net result of this four-pronged attack on property was to pump up demand with all those freshly-printed dollars while raising the cost and restricting the supply of the stuff they wanted to spend them on.

No wonder we saw a housing bubble.

No wonder price inflation on housing (which is all those price really increases were) went through the roof.

No wonder so many people were deluded by the price inflation into thinking they were becoming rich-instead of just seeing their dollars devalued.

No wonder land prices now account for up to 60% of the cost of a house in Auckland.

No wonder new homes tend to be at the top-end of the market.

No wonder things began to become insane, with the cost to build a house beginning to outstrip even the cost people were prepared to pay for it—meaning the model for speculative housing*** (which has for decades been building the means by the vast majority of new affordable homes was built) is now permanently broken.

How do we do that?

Simple. We stop what should never have been started.

We get rid of fiat money; we get rid of zoning; we shut planners up and put a stake through the heart of their Resource Management Act; we stop fighting so-called “sprawl” with “Urban Walls” and instead leave people free to develop their own land according to demand.

In short, we give power back to builders and property owners to do what they do best while taking power away from those who only get in their way.

Yes, government could do more. It could do a whole lot more by doing a whole heck of a lot less.

And Bernard Hickey et al could either write less, or learn more.

* * * * *

* The Productivity Commission in its recent report on affordable housing is only half-way there with its own solution, but it would at least be a start. The Commission’s key recommendations include:

-

The urgent need for more land to be opened up for housing, especially in urban areas, because sections now average about 40% to 60% of the cost of a house.

-

Reconsideration of Auckland’s draft spatial plan. Auckland faces significant housing affordability challenges and the Commission found its current plan, with a target of accommodating 75% of new homes within existing urban boundaries, will be difficult to reconcile with affordable housing.

-

Improved processes for consenting, to speed up the service and lower costs.

-

Improving how local council development charges for infrastructure are calculated and applied, including making them reviewable. The Commission found the current model has too much regional variation and is not transparent.

Perhaps Mr Hickey and Ms King could read them?

** As the Annual Demographia Surveys ( www.demographia.com ) clearly illustrate - households should not be paying any more than 3 times their annual household income to house themselves - with mortgage loads around 2.5 times. Unfortunately in all NZ’s major cities home-owners are now paying from 6 to 8 times their annual household income to house themselves , a figure that increases ever year.

*** What is speculative house building? It’s when Joe Builder buys a site, builds a house on it, and sells it to Mr and Mrs New-Home-Owner for more than he’s shelled out—giving him a small profit which he can use to build his next one. This is how “spec” houses have been built since Adam was a lad—but now can’t be. Because that model has been made unaffordable.

UPDATE 1: The government’s housing affordability moves are reported as:

- increasing land supply, including greenfield, brownfield and further densification;

- minor RMA changes, including a 6-month time limit on processing medium-sized consents;

- improving timely provision of infrastructure to new housing, including “new ways” to coordinate and manage infrastructure;

- improving productivity in the construction sector (how? somehow)

Given that the last of these four looks like nothing more than wishful thinking (magical thinking?), and the first three areas are actually under the control of councils not central government, and no plans have been announced to take any of that power away (or to indicate how efficiencies and timeliness might be achieved), then they might as well have added “and a new pony.”

1 comment:

I watched some of the interview with English and was pretty disheartened with all his talk of "a more balanced economy" and "a common sense of purpose". I turned it off before the end of the interview thinking, "what the f*** is he on about?"

If he does anything to get more affordable houses built by the private sector, I'll eat my copy of the Resource Management Act.

Post a Comment